Intro

For whatever reason, mathematicians like thinking up puzzles where a bunch of prisoners have to perform some math under adversarial opposition from the guards, with freedom or execution as motivators. For instance, 100 prisoners are lined up facing forward, with either white or black hats, and they have to determine if their own hat is white or black. Or the Veritasium video about boxes and numbers.

I recently thought of a puzzle like this, involving graph theory. Let's say you have N prisoners. They will be led, one-by-one, into a room. In that room, they will collectively construct a simple, undirected graph. Each of them places exactly 1 vertex, and they can add any edges to the graph that they want. The graph starts empty, so for N prisoners it will end up with N vertices. The prisoners cannot speak to one another, or change the room aside from their additions to the graph.

Between each prisoner, guards can come in and move or rearrange the vertices of the graph however they like. They cannot add or remove vertices or edges, and so they cannot change the underlying structure of the graph.

To put a more physical aspect to this: imagine the prisoners are placing small, identical-looking balls in the room, one each. They can connect the balls with identical lengths of string. Each ball looks the same on the outside, but inside has the prisoner's ID, so we can still tell which is which, just not from looking at it. The guards cannot add or remove any balls or string, but they can move them around, so the prisoners can't rely on position or orientation to distinguish them.

After the graph is made, the prisoners (still unable to communicate) are then led through again one at a time. From viewing the finished graph, they need to identify which vertex they placed. As in, they point to the the vertex/ball they think is theirs, at which point the guards can check its internals to confirm or deny it.

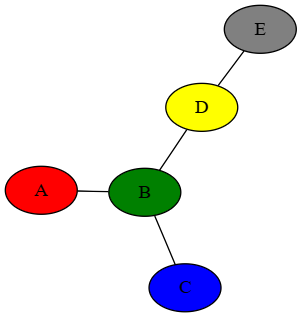

For instance, maybe they convert this graph:

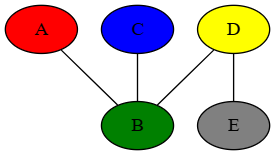

Into this one:

The colors/labels are just there for demonstration: remember, to the prisoners each vertex looks the same. In this case, you could probably pick out B in the second graph (it's the only vertex connected to 3 others), and from there D and E as well. But A and C are ambiguous, and can't be told apart.

The question is: what strategy can we use to guarantee as many prisoners as possible succeed in identifying their vertex correctly on this second round?

I like graph theory, but I will not pretend to be good at it. If you're interested, look for other learning sources that aren't me.

If you'd like to take a moment and think this through, now would be the time. Otherwise, I'll talk more about the math behind it, and then my own thoughts on what I think the answer is.

spoiler warning

spoiler warning

spoiler warning

spoiler warning

spoiler warning

spoiler warning

My Initial Solution

So first off, the topic in graph theory that will probably be useful here is asymmetric graphs. These are graphs where no matter how you move the vertices, the structure alone is fully unique for each vertex. If I show you a labeling of each vertex, then move the vertices around, you'll always be able to identify the original labeling post-shuffle. The minimum such graph has 6 vertices (Wikipedia has a list of them).

This also relates to group theory, in that we care about automorphisms of a graph: symmetries where we can permute the vertices without changing the structure of the graph. An asymmetric graph has no automorphisms (or more pedantically, it only has the trivial automorphism: the singleton).

A natural strategy might then be: have the first 6 prisoners sacrifice themselves, and construct one of the asymmetric graphs. Each prisoner after that can add a vertex that keeps the graph asymmetric. In the end, prisoners 7 and beyond can find their vertex in the final graph by looking for the subgraph that they saw when they entered the room, and using that to locate their own vertex.

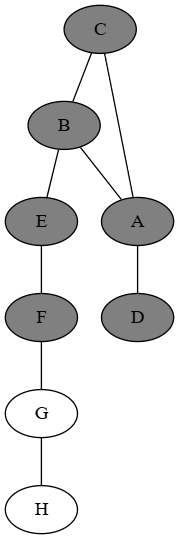

So...how do we do construct a sequence of asymmetric graphs by adding a vertex and some edges each time? I thought about this for a while, and it seems like an interesting problem. Then I realised we could just do this:

As long as we put the chain on that vertex (extending from the 2 vertex chain on the triangle), we can keep it going forever, and the structure is always unambiguous: you know where in the chain you were, and there's only one vertex like that in the graph.

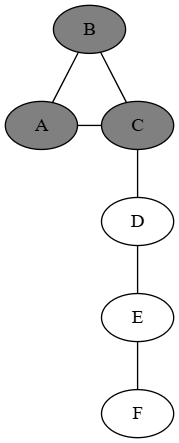

But can we do better? I then thought about this graph:

which only requires 3 sacrifices. Despite there being no asymmetric graphs with 4 vertices, we don't actually need it to be fully asymmetric: it just needs to let us disambiguate at least some vertices.

Optimal solution?

Can we do even better than that? I believe this is a similar construction that lets us save all but 2 prisoners:

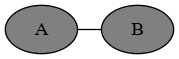

The first two prisoners make a graph that has 2 vertices (let's say A and B), along with an edge between them:

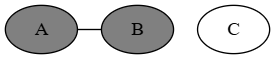

the third prisoner adds their vertex (call it C), but does not add any new edges:

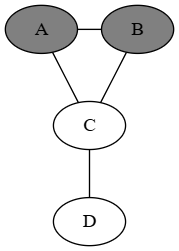

Then, the fourth prisoner adds their vertex (vertex D). They connect C to A, C to B, and D to C:

And then we continue as before. In this way, the third prisoner is able to tell that their vertex ended up as the lynchpin b/w the triangle and the chain. Meaning N - 2 prisoners are saved.

So...is that the limit? I think it is. After the first two prisoners have gone, we only have two possibilites:

A graph of 2 vertices that are disconnected

A graph of 2 vertices with an edge b/w them

In either case, the guards can move these around and keep it ambiguous as to which is which. No matter what they do, or what the third prisoner does, there's no way to recover which of A and B is which. They can guess of course with a 50% chance, but as far as I can tell that's the limit.

But, I haven't actually proven anything rigorously. If you think I got it wrong, lemme know on Mastodon.

Addendum

Some variations to consider:

What if they can remove edges and also add them?

I don't think this makes a difference

What if they start with an existing graph before any of them enter?

With 1 vertex, this seems like it can push it to (N - 1)

With 2 vertices or more, this seems like it can be pushed to all N

Does it matter if the prisoners can then talk b/w the graph being finished, and the 2nd round?

Probably still no: the ambiguities can't be resolved even w/ this information

What if you allow loops (a vertex connected to itself), or ordered edges?

I think these let you guarantee all N prisoners guess right

For loops: first prisoner adds a vertex, and then a loop. All prisoners after build a chain, and the loop vertex disambiguates the orientation, so everyone can find their own vertex

For ordered edges: I couldn't figure it out, but I'm confident you can figure it out for me

^_^

Addendendum

I searched as well as I could, and did not see this problem in any pre-existing literature: it's entirely plausible it's tucked away in some math textbook, puzzle collection, or competition math practice sheet. I even tried asking various LLMs: Anthropic's Claude 4.5 said it was novel (which it often does, even when something isn't novel), while GPT5 and Gemini 3 both gave made-up references, even after I pointed it out.

LLMs also seem to get completely confused trying to solve the problem. They immediately realise, "oh, this is about asymmetric graphs and graph automorphisms", but they either said it could be done with all prisoners succeeding, or could only be done with 6 sacrifices. I tried re-phrasing the problem several times, but they didn't get it. I even enabled "thinking" and "web search" and "please god just stop being stupid" but nothing.